Biologic Chromoendoscopy – The Eye Beats Artificial Intelligence

By Klaus Mönkemüller, MD, PhD, FASGE, FJGES

Professor of Medicine, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, USA

Natural or Biologic Chromoendoscopy for Detection of Colorectal Polyps

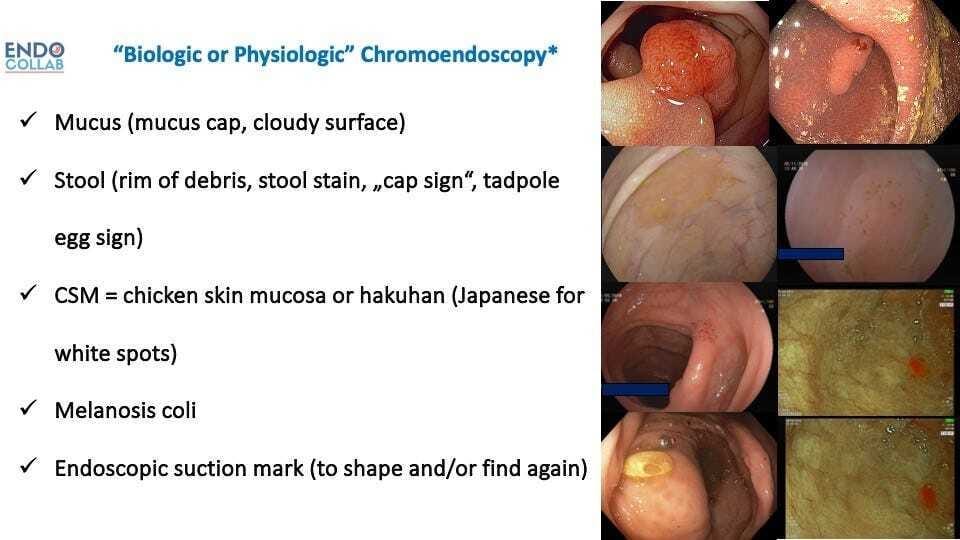

Endoscopic detection and resection of colorectal polyps is the key determinant for eventual prevention of colorectal cancer. Whereas visualization of sessile and pedunculated colon polyps is relatively straightforward and easy, finding flat or sessile serrated lesions is more challenging, more so for visual aid systems using artificial intelligence, or traditional virtual or dye-based chromoendoscopy techniques, as these lesions tend to secrete mucus or accumulate debris, or stool on their surface (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Personal Classification of Biologic or Natural Chromoendoscopy.

We have called this spontaneous or natural way of changing or adding color to the surface “biologic or natural chromoendoscopy”. The presence of mucus affects the coloration of the serrated lesions in three possible ways: a) the thicker mucus layer changes light penetration onto the mucosa, thus making the lesions appear paler, b) the mucus serves as a trap for debris and stool, and c) the presence of mucous filaments give the lesion a distinctive hazy appearance. In serrated lesions there are 2 consistent and unequivocal changes affecting goblet cell mucin secretion: loss of O-acetyl substituents at sialic acid C4 and C7,8,9 increase sialylation (1). Other biologic chromoendoscopy presentations are “chicken skin mucosa” and melanosis coli (Figure 2).

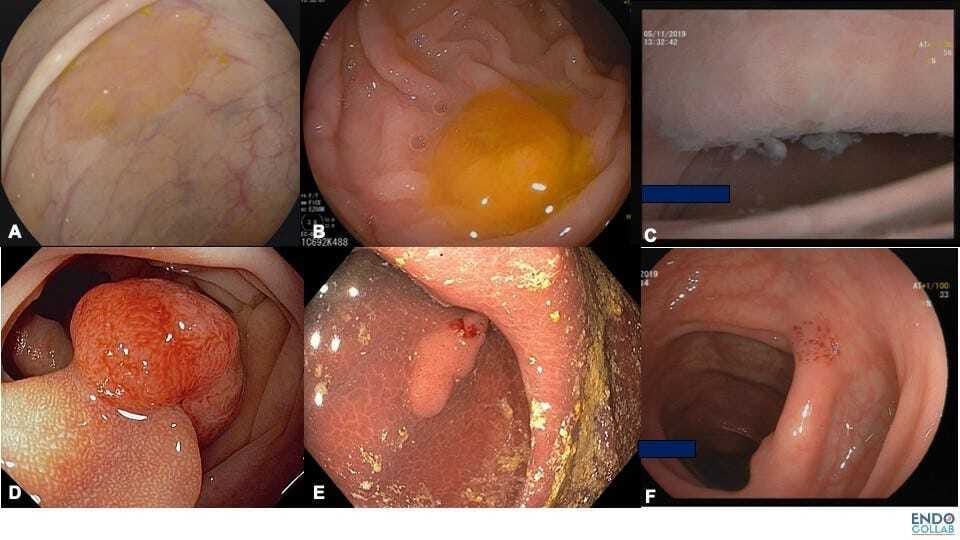

Figure 2. Various Types of Biologic or Natural Chromoendoscopy. A. Rim of stool or mucus. B.Cap of stool. C. Cloudy surface.D. Hakuhan or chicken skin mucosa. E. Melanosis coli. F.Endosocpic suction mark

Whereas chicken skin mucosa is present in sessile and/or neoplastic lesions, melanosis coli improves the detection of quasi any colorectal polyp. Chicken skin mucosa was described in Japan in 1981 and termed “hakuhan”, which means “white spots” (2). The term chicken skin mucosa was introduced in 1998 by Shatz et al. (3). The found that CSM was associated frequently with adenomatous polyps and adenocarcinoma. Histologically, CSM is caused by an accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages. Subsequently, Nowicki et al found that CSM is found in up to 75% of juvenile polyps. By using CD68 satins, which is specific for macrophages, the authors confirmed that CSM is due to lipid-laden macrophages and not associated with increased malignancy (4).

Melanosis coli is characterized by dark appearance of the colorectal mucosa, with the depth of color varying between pale grey and brown or black.

The dark deposit in the lamina propria is not melanin as the name suggests, but lipofuscin.

It’s association with the use of anthraquinone laxatives, including senna, aloe and rhubarb, rhamnus, and frangula has been known for almost 100 years.

Senna glycoside (senna) is the main causative laxative (5). As the laxative travels down the GI tract, it remains in its inactive form until it reaches the colon, where the molecules are activated, leading to colonocyte damage and death (5). As these cells undergo apoptosis, they create a dark pigment, lipofuscin, which eventually is deposited in the lamina propria. Eventually, these dead cells are taken up by macrophages. Interestingly, melanosis coli can occur within only a few months of chronic laxative use (5).

We believe that knowledge of this characteristic of various flat and serrated lesions is important for the practicing endoscopist, as it will improve the detection and characterization of these colorectal lesions. More importantly, current artificial intelligence systems lack the ability to specifically recognize flat lesions based on biologic chromoendoscopy, and thus the human eye and brain needs to stay cognizant of this aspect.

References:

Jass JR J.R. and Roberton AM., Colorectal mucin histochemistry in health and disease: a critical review. Pathol Int 1994;44; 487–504.

Muto T, Kamiya J , Sawada T, Sugihara K, Kusama S. Clinical and histological studies on white spots of colonic mucosa around colonic polyps with special reference to diagnosis of early carcinoma. Gastroenterological endoscopy, 1981;23:2:241-247

Shatz BA, et al. Colonic chicken skin mucosa: an endoscopic and histological abnormality adjacent to colonic neoplasms. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:623–7.

Nowicki, M et al. Colonic Chicken-Skin Mucosa in Children with Polyps is not a Preneoplastic Lesion, Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2005;41:600-606.

Nesheiwat Z, Al Nasser Y. Melanosis Coli. [Updated 2023 Feb 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493146/