Gastric Volvulus

Discover the types, symptoms, and management of gastric volvulus through an 87-year-old patient's case study. Learn about organoaxial and mesenteroaxial volvulus, and their clinical implications.

Gastric Volvulus

Julika S. Loew, MS, Josip Juraj Strossmayer Universität Osjiek, Croatia, Ameos Klinikum Halberstadt, Germany

Klaus Mönkemüller, MD, PhD, FASGE, FJGES, Professor of Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, Ameos Klinikum Halberstadt, Germany and Carilion Memorial Hospital, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, USA

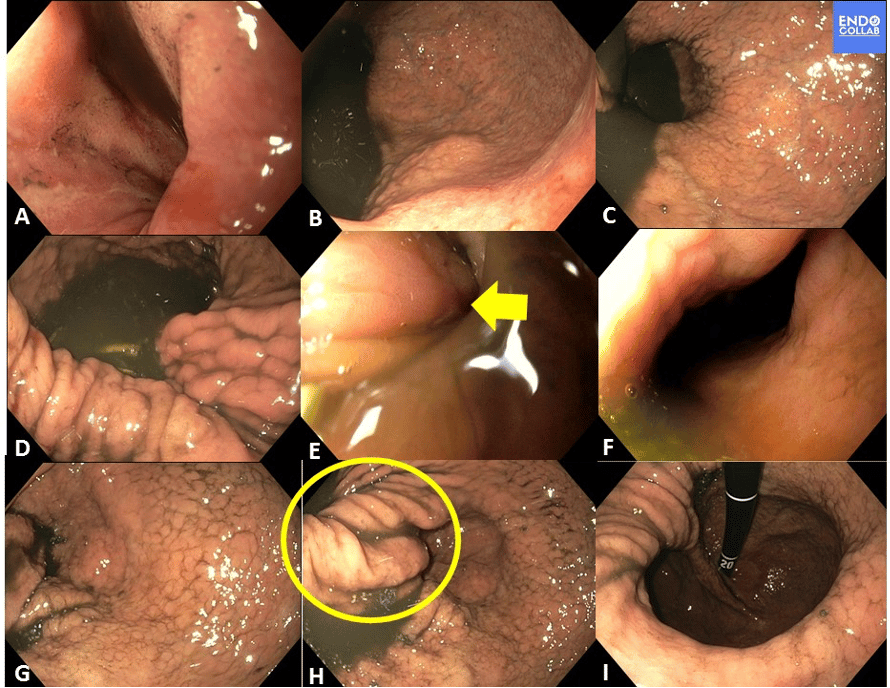

An 87-year-old lady was admitted because of sudden onset thoracoabdominal pain, relentless vomiting, and coffee-ground emesis. After life-threatening cardiopulmonary conditions had been ruled out she underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Organoaxial gastric volvulus. A. Massively edematous cardia. B. Part of the fundus is transferred to the right side (the fundus is usually located on the left side unless the patient has situs inversus). C. Retained stomach fluid is coming from the left side. D. Large amount of fluid in the “twisted” stomach (we suctioned about 1500 ml through the endoscope). E. The arrow shows the “twisting point” in the middle of the stomach body. F. By applying air, the opening could be opened and then scope advanced through the body of the stomach to the pylorus. G. Massive mucosal edema due to congestion. Ongoing volvulus (“twisting”) can result in necrosis. H. The twisted stomach body is clearly seen (yellow circle). I. After “untwisting” the stomach we performed retroflexion, which shows a humongous hiatal hernia of about 9-10 cm diameter.

Gastric volvulus is a rare, challenging condition, defined by the abnormal rotation of the stomach, which can be classified based on the axis of rotation, being either along the stomach’s short or long axis (1, 2). It often clinically presents with the Borchardt triad referring to sudden onset of constant epigastric pain, recurrent retching with vomiting and inability to pass a nasogastric tube.

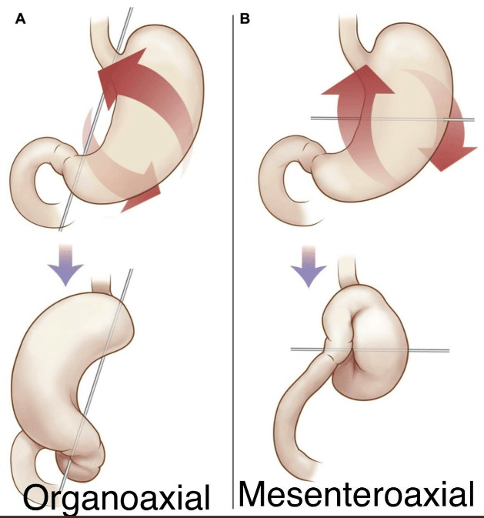

It is important to recognize two forms of gastric volvulus (Figure 2):

Fig. 2: Gastric volvulus (Attribution: Terry Helms, Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital, USA)

Type I being the organoaxial volvulus (OA), commonly occurring in the setting of trauma or large paraoesophageal hernia. The stomach is rotated along its long axis, which is drawn between the cardia and the pylorus. A complete rotation over 180° usually results in obstruction or ischemia, whereas an incomplete rotation is usually asymptomatic.

Type II is mesenteroaxial volvulus (MA) is less commonly seen in adults, but more common in the pediatric population (59% of gastric volvulus) (1, 2). It is characterized as a rotation around the short axis, causing “bisection” of greater and lesser curvature of the stomach. It coincides with the axis of mesenteric attachment and is often associated with severe strangulation and obstruction (1, 2). This type of gastric volvulus is less commonly associated with diaphragmatic defects. The mesenteroaxial volvulus volvulus usually presents as a chronic disease, with its etiology being idiopathic (2) Predispositions to mesenteroaxial volvulus rotations are diseases of the stomach, like peptic ulcers, which cause a retraction of the small curvature.

Type III is the combination of the mentioned types.

Further classification is based on etiology as primary or idiopathic causes: tumors, adhesion, problems in normal ligamentous attachments of stomach and secondary causes: disorders of gastric motility and anatomy, issues of neighboring structures like diaphragm and spleen. Most cases have a secondary cause in adults, usually associated with para esophageal hernia and traumatic diaphragm injury. (2)

In our case, patient has Type I organoaxial volvulus based on a paraoesophageal hernia Type IV.

The initial management of gastric volvulus is decreasing intragastric pressure through nasogastric or endoscopic decompression.

In the following, surgery must be performed to check gastric viability and resect necrotic tissue. Volvulus is treated with detorsion and fixation of the stomach by gastropexy, in case of a diaphragmatic defect, hiatal hernia has to be repaired (1, 2). In asymptomatic patient, expectant nonoperative management is advised.

References:

1. Niknejad MT. Gastric volvulus | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org

2. Akhtar A, Siddiqui FS, Sheikh AAE, Sheikh AB, Perisetti A. Gastric Volvulus: A Rare Entity Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. 2018 Mar 12;10(3):e2312. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2312. PMID: 29755908; PMCID: PMC5947932.

None of the authors (JSL, KM) have any COI to declare.

Join EndoCollab: Your Gateway to Endoscopy Excellence!

Are you ready to transform your endoscopy practice? Join EndoCollab today and gain access to:

1000+ cutting-edge endoscopy strategies

A global network of 1200+ endoscopists

Expert-led video courses

Comprehensive Endoscopy Atlas for visual learning

Personalized learning paths for your career stage

Whether you're a fellow mastering basics or an experienced practitioner exploring advanced techniques, EndoCollab is your path to confidence and excellence.

"EndoCollab is the greatest learning opportunity seen in GI endoscopy so far."

Dr. Pablo Cortegoso

Join now and elevate your skills:

Monthly: $14.99

Yearly: $149 (Save 2 months!)

Lifetime Access: $399

Don't miss out on this opportunity to grow your expertise and connect with peers worldwide.