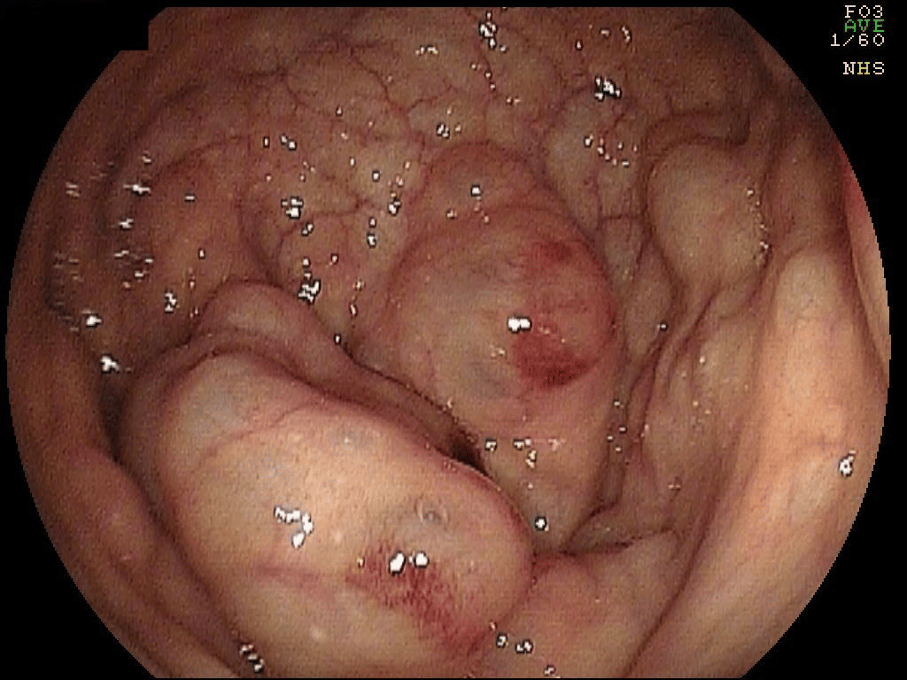

Multiple Polypoid Sigmoid Colon Lesions

An elderly patient presented with abdominal pain, diarrhea and fever. A colonoscopy was performed about 10 days after the initial symptoms had improved. At that point the main indication for colonoscopy was the presence of mild hematochezia. What is the diagnosis?

When discovering polypoid lesions in the colon, the endoscopist should characterize those. How many polypoid lesions are present? What is the colonic distribution? How does the mucosa appear? Do the polypoid lesions express a “pit pattern”? What is the color of the lesions? Are there any associated findings? What is the consistency of the lesions?

In this case there were about 20 to 25 polypoid lesions ranging from 10 to 30 mm in size located in the sigmoid colon. The mucosa overlying the lesion was normal without any specific pit pattern or ulcerations. However, some areas of erythema were present on few of them. The polypoid lesions were soft and appeared as “blebs”. There were no other associated mucosal findings.

Answer: Pneumatosis coli

This is the characteristic endoscopic and descriptive appearance of multiple gaseous cysts inside the bowel wall or pneumatosis coli, also known as pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis or pneumatosis intestinalis, whereas the latter mainly refers to small bowel involvement.

Pneumatosis can present in children, usually in premature infants, as a consequence of the life-threatening condition necrotizing enterocolitis. In adults there are life-threatening and “benign” forms. Life-threatening pneumatosis can originate from ischemia, bowel obstruction, enterocolitis, toxic megacolon and collagen vascular diseases (1). Benign etiologies include COPD, transient ischemic colitis, gastroenteritis, collagen vascular diseases, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and organ transplantation. Importantly, the benignity of the pneumatosis does mainly depend on the clinical presentation of the patient, as many of the etiologies are not certainly “benign”.

As you noticed, there are lots of potential etiologies, indicating that the mechanism of injury must be different. These mechanism for bleb formation include: a) pulmonary disease leading to pneumomediastinum with gas travelling or tracking through the peri- mesenteric vessels to the gut, b) bacterial gas production (during gastroenteritis), c) disarrangement of the microbioma with dysbiosis and promotion of gas-forming organisms, d) local mucosal damage due to toxins, drugs and hormones, and e) ischemia with gas entrapment following regeneration of the epithelium and submucosa.

Histology is usually not needed for the diagnosis. The outcome of pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis depends on the primary diagnosis. In the present case, the triggering event (transient ischemic colitis or gastroenteritis) had already subsided and the patient was doing well. Therefore, no additional endoscopic or medical therapy was instituted.

References:

1. Ho LM, Paulson EK, Thompson WM. Pneumatosis intestinalis in the adult: benign to life-threatening causes. (2007) AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 188 (6): 1604-13. doi:10.2214/AJR.06.1309

2. Jacob T, Paracha M, Penna M, et al. Pneumatosis coli mimicking colorectal cancer. Case Rep Surg. 2014;2014:428989. doi: 10.1155/2014/428989. Epub 2014 Oct 7. PMID: 25400972; PMCID: PMC4220578.

very interesting, thanks for sharing

Great Case and Nice Pics Congrats